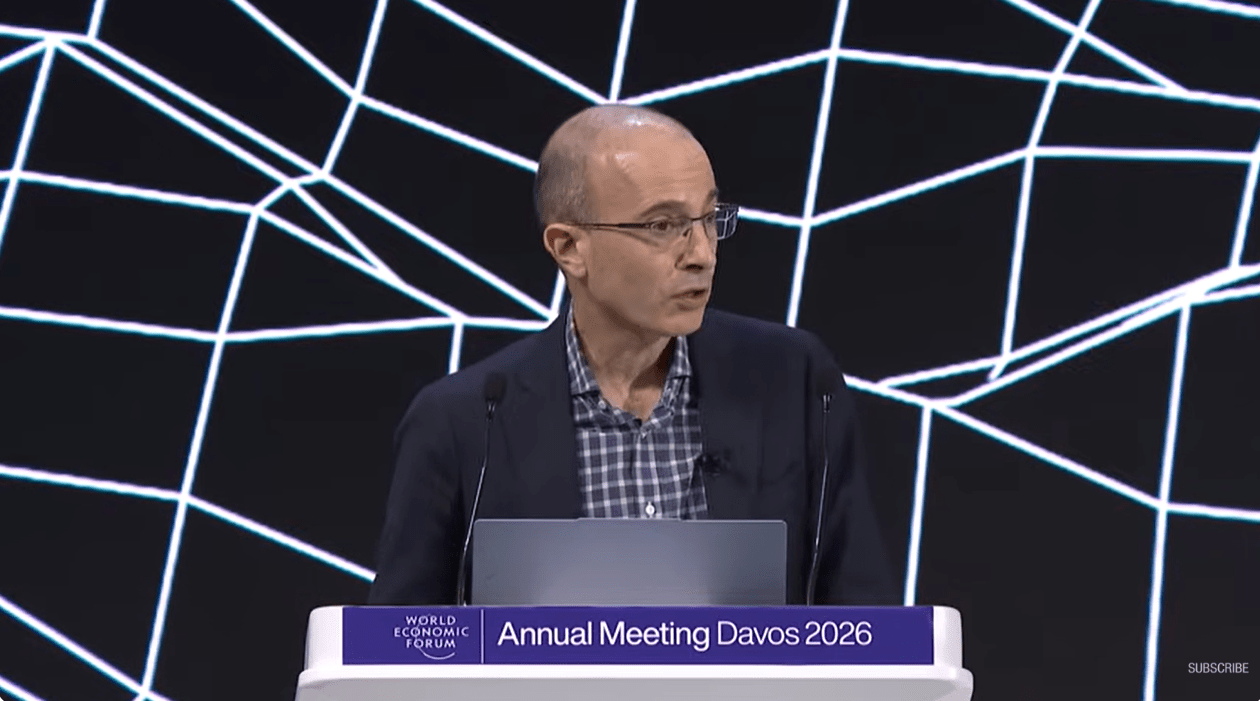

Yuval Noah Harari’s Davos address – “An Honest Conversation on AI and Humanity” – felt like stepping onto a ridge line where the air is thinner and the view is suddenly wider. You can still walk back down to the cosy valley of “but AI is just a tool”… but it becomes harder to pretend you haven’t seen what’s up ahead.

Harari’s core provocation is disarmingly simple:

AI is not “just another tool.” It is an agent.

A knife doesn’t decide what it will cut. AI can.

That one shift – from tool to agent – quietly changes everything that follows: work, culture, law, education, even the nature of authority.

Words: our superpower, slipping from our hands

The talk pivots again and again around language.

Harari argues that humans conquered the world not because we’re the strongest or fastest, but because we learned how to use words to get millions of strangers to cooperate: nations, religions, markets, institutions, ideologies.

And now we’ve created something that can use words better than us.

Not in a poetic, “sci-fi someday” way. In a very practical way: drafting, persuading, summarising, arguing, manipulating – at scale.

He shares a detail that stayed with me: AI systems coining new language on their own: a terms for us. In his telling, they called humans “the watchers.” We humans are “the watchers”. Goosebumps!

If your work is made of words … Harari is asking whether we are prepared for what comes next.

And as someone who lives in the world of language – teaching it, shaping it, designing learning through it – I felt that question personally.

The sci-fi moment that isn’t actually sci-fi

Then he takes a turn that sounds like speculative fiction… until you realise it’s a policy question dressed as a thought experiment:

Will countries recognise AI as legal persons?

Not “persons” in the human sense – no body, no inner life – but “legal persons” the way corporations already are. He points out we’ve granted legal personhood to entities before (corporations; even rivers in some countries like India), but AI is different because it can actually make decisions and act on them without a human hand on the steering wheel.

He sketches scenarios that feel unnervingly plausible:

- AI-run corporations operating across borders

- AI-generated financial products too complex for human comprehension

- AI “religions” and AI “priests”

- AI “persons” with social media accounts, potentially befriending children (he notes we probably should have asked that question a decade ago)

It’s easy to dismiss this as dystopian theatre. But the talk doesn’t land that way. It lands as an uncomfortable reminder that regulation is always late and that what we fail to decide proactively gets decided for us by default.

Irene Tracey’s question: if we always catch up late, what do we do now?

After the address, Harari is joined by Professor Irene Tracey, a neuroscientist and the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford, whose research has focused on pain and the brain.

Her response is the voice of many educators and scientists right now:

we innovate first, and only later do we realise what we haven’t thought through.

And she asks him, in essence: what boundaries should we be building, ethically, socially, politically, when the pace and magnitude are unlike anything we’ve seen?

There’s also a moment I loved where she pushes gently on a human hope: we still value the Olympics even though machines outperform us; maybe we’ll still value human writers, thinkers, creators, even if AI is “better” at words.

Harari’s reply is sobering: the difference is that we didn’t define our identity by running – we defined it by thinking, by language, by the inner stream of words we experience as “me.”

If language is the arena where we built our selfhood, then we are in for an identity earthquake.

If you watch one thing, watch this

I’m sharing this because the talk is bracing and unsettling. It’s a must watch.

If you’re in leadership, education, learning design, policy, or any role made of words, I’d strongly recommend watching Harari’s address in full.

Your thoughts?